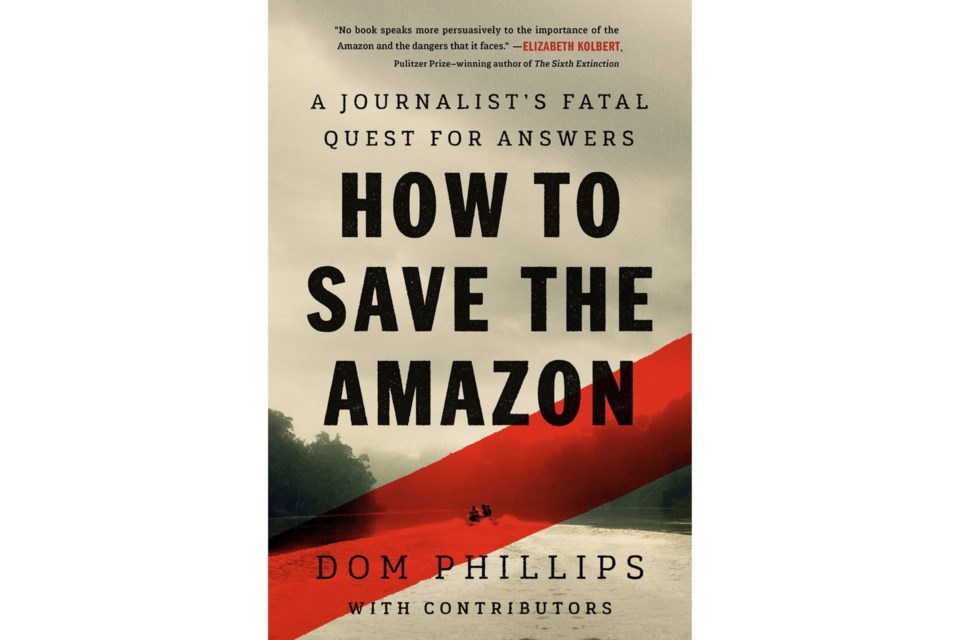

BRASILIA, Brazil (AP) ā After British journalist Dom Phillips was shot and killed while researching an ambitious book on how to protect the worldās largest rainforest, friends vowed to finish the project. Three years later, their task is complete.

āHow to Save the Amazon,ā published Tuesday in Brazil and the United Kingdom ahead of its U.S. release, was pieced together by fellow journalists who immersed themselves in Phillipsā notes, outlines and the handful of chapters heād already written. The resulting book, scheduled to be published in the U.S. on June 10, pairs Phillipsā own writing with othersā contributions in a powerful examination of the cause for which he gave his life.

In addition to the core group who led the work on finishing the book, other colleagues and friends helped to edit chapters, including The Associated Press journalists Fabiano Maisonnave and David Biller.

Phillips, who had been a regular contributor to The Guardian newspaper, was taking one of the final reporting trips planned for his book when he was gunned down by fishermen on June 5, 2022, in . Also killed was Bruno Pereira, a Brazilian expert on Indigenous tribes who had made enemies in the region for defending the local communities from intruding fishermen, poachers and illegal gold miners. made headlines around the world. Nine people have been in the killings.

āIt was just a horrifying, really sad moment. Everybody was trying to think: How can you deal with something like this? And the book was there,ā said Jonathan Watts, an Amazon-based environmental writer for The Guardian who coauthored the foreword and one of the chapters.

With the blessing of Phillipsā widow, Alessandra Sampaio, a group of five friends agreed to carry forward. The group led by Watts also included Andrew Fishman, the Rio-based president of The Intercept Brasil; Phillipsā agent, Rebecca Carter; David Davies, a colleague from his days in London as a music journalist; and Tom Hennigan, Latin America correspondent for The Irish Times.

āIt was a way to not just feel awful about what had happened, but to get on with something. Especially because so many of Domās friends are journalists,ā Watts said. āAnd what you fall back on is what you know best, which is journalism.ā

Unfinished work researching rainforest solutions

By the time of his death, Phillips had traveled extensively across the Amazon and had completed an introduction and nearly four of the 10 planned chapters. He also left behind an outline of the remaining chapters, with different degrees of detail, and many pages of handwritten notes, some of them barely legible.

āI think itās fair to say even Dom didnāt yet know what he would do exactly in those chapters,ā Watts said.

Phillips was searching for hope. He promised his editors a character-driven travel book in which readers would get to know a wide-ranging cast of people living in the area, āall of whom know and understand the Amazon intimately and have innovative solutions for the millions of people who live there.ā

The group led by Watts selected writers for the remaining chapters, with subjects ranging from a bioeconomy initiative in Brazilās Acre state to global funding for rainforest preservation. Indigenous leader Beto Marubo of the Javari Valley was recruited to co-write an afterword. The team also launched a successful crowdfunding campaign to pay for more reporting trips.

Among the groupās challenges was ensuring that the book reflected a political shift in Brazilās approach to the Amazon in the years since Phillipsā death. Most of Phillipsā research was done during the term of right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro, as Brazilās Amazon deforestation reached a in 2021. The pace of destruction 2022 defeat by leftist leader Luiz InĆ”cio Lula da Silva.

Fragments of hope, grim statistics

Throughout the finished bookās more than 300 pages, fragments of hope mix with grim realities. In Chapter 2, āCattle Chaos,ā Phillips notes that 16% of Brazilās Amazon has already been converted to pasture. Even a farmer who has become a model for successfully increasing productivity without clearing most of his land is criticized for his widespread use of fertilizers.

In his chapter on bioeconomy, journalist Jon Lee Anderson visits a reforestation initiative where Benki leader, promotes environmental restoration coupled with ayahuasca treatment and a fish farm. But the veteran reporter doesnāt see how it can be scalable and reproducible given man-made threats and climate change.

Later in the chapter, he quotes Marek Hanusch, a German economist for the World Bank, as saying: āAt the end of the day, deforestation is a macroeconomic choice, and so long as Brazilās growth model is based on agriculture, youāre going to see expansion into the Amazon.ā

In the foreword, the group of five organizers state that āLike Dom, none of us was under any illusion that our writing would save the Amazon, but we could certainly follow his lead in asking the people who might know.ā

But in this book stained by blood and dim hope, there is another message, according to Watts: āThe most important thing is that this is all about solidarity with our friend and with journalism in general.ā

___

The Associated Pressā climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find APās for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at .

Fabiano Maisonnave, The Associated Press