Bruce Davidson remembers the E. coli outbreak that ravaged his hometown 25 years ago as a "strange dream."

The hospital in the small Ontario community of Walkerton usually wasn't busy but it suddenly got inundated with patients experiencing severe diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain. The first cases were reported on May 17, 2000.

Soon, the township roughly 140 kilometres north of London, Ont., ran out of diarrhea medication, the emergency department overflowed and air ambulances came to take sick people to other hospitals.

What turned out to be Canada's worst outbreak of E. coli O157 infections, caused by manure-tainted drinking water, ultimately killed seven people and sickened around 2,300.

It was a "strange dream where you're still you but nothing else is the same," said Davidson. His own family fell ill and he later formed a citizens' advocacy group in response to the tragedy.

Schools and restaurants were closed, he said, and streets that normally buzzed with children playing on warm spring days felt like a "ghost town."

"For the first bit, we were all in shock, but very, very quickly that started to change to anger," Davidson said in a recent phone interview.

He had heard about waterborne diseases in impoverished parts of the world, but said he never imagined experiencing that in Canada.

The country had the technology, money and infrastructure needed for a safe water supply, "and yet here we are killing people with drinking water," he said.

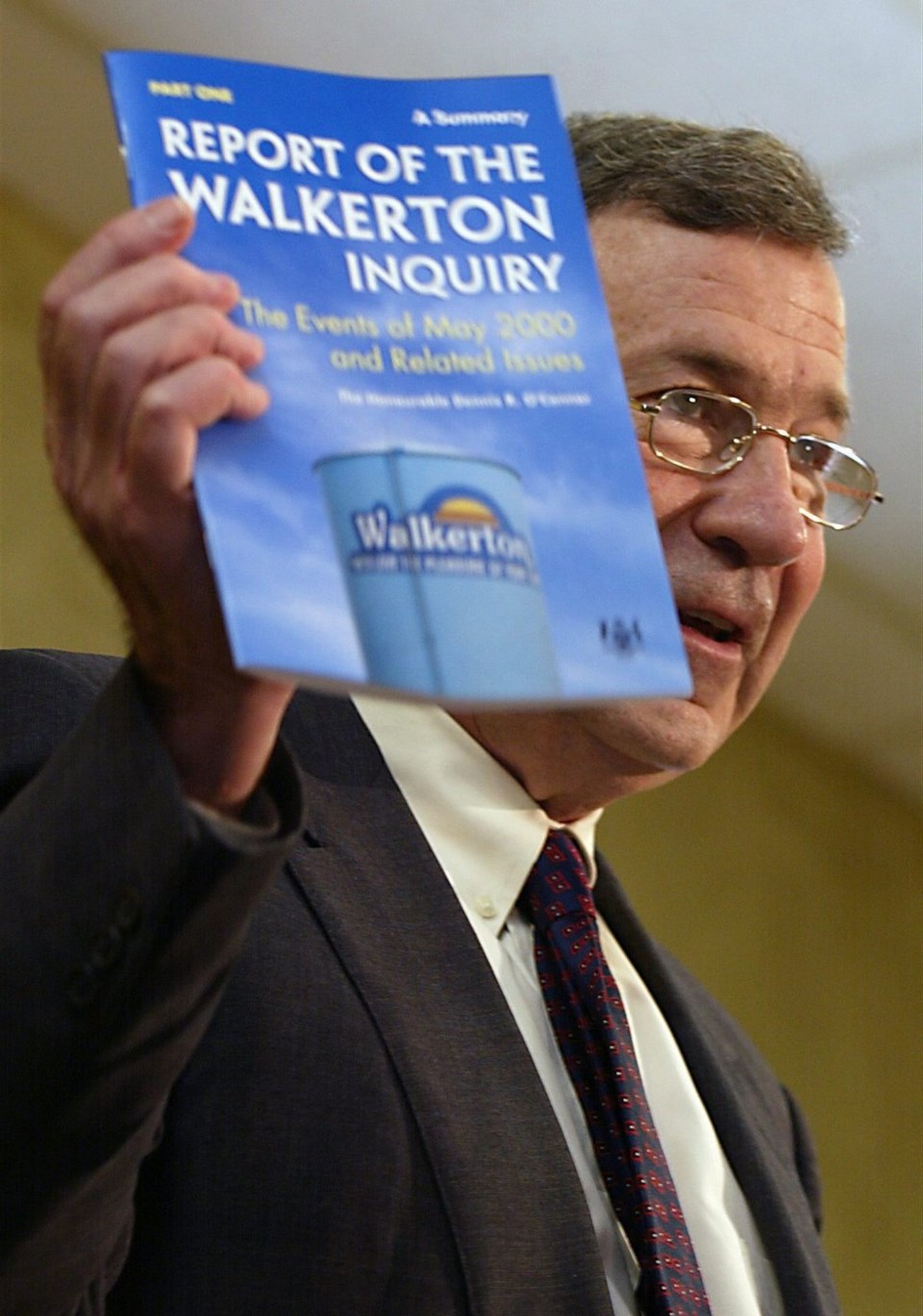

The health crisis caused by a mix of human negligence, lack of resources and natural factors caused countrywide outrage and triggered a public inquiry led by Ontario Justice Dennis O’Connor that lasted for nearly two years.

It was determined that heavy rainfall between May 8 and May 12, 2000 had washed cattle manure from a nearby farm into a well. From there, deadly E. coli bacteria found its way to the municipal water system.

The two brothers who managed the system — Stan and Frank Koebel — pleaded guilty to criminal charges in the case.

The inquiry found that neither brother had the formal training to operate a public utility and water system, that they failed to properly chlorinate the water and that water safety records were falsified.

The inquiry also found that Stan Koebel knew on May 17 that water was contaminated with E. coli but he did not disclose those test results for days. By the time a boil-water advisory was issued on May 21, it was too late.

"It was extremely tragic and even more tragic by the fact that the operators who didn't have proper training and didn't understand that groundwater could make people sick were suppressing the results of tests," said Theresa McClenaghan, the executive director of the Canadian Environmental Law Association.

McClenaghan, who represented Walkerton’s residents during the inquiry, said had the brothers been transparent and told the public about the issue as soon as they knew, many would not become ill.

"But that went on for days and days that people were still drinking this highly contaminated water," she said.

McClenaghan said the inquiry didn’t leave any stone unturned and in the end put out a series of recommendations that now serve as the foundation of water safety regulations, including the province's Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act.

The tragedy led to fundamental legislative reforms aimed at strengthening drinking water safety norms, including water source protection, treatment standards, testing and reporting procedures.

Despite the huge progress, access to safe drinking water is still a serious issue, especially in northern Ontario's First Nations communities.

A report released by the Ontario's auditor general in March raised concerns about oversight of non-municipal water systems that include inadequate testing and monitoring and lack of compliance enforcement. Nearly three million Ontarians get their water from a non-municipal system.

While 98 per cent of samples tested from these systems in the past decade have met the provincial drinking water standards, there are weaknesses that need to be addressed to ensure water safety, the report said.

It said about 1.3 million people drink water from private wells, and 35 per cent of the samples taken from them between 2003 and 2022 tested positive for indicators of bacterial contamination.

The report listed recommendations that include increasing testing and oversight, and raising awareness about the risks and availability of testing resources.

"As demonstrated by the Walkerton crisis, the consequences of Ontarians drinking unsafe water can be deadly," auditor general Shelley Spence wrote.

The Canadian Environmental Law Association and dozens of other organizations have written to the provincial government calling for a "timely and transparent" implementation of Spence's recommendations.

The mayor of Brockton, Ont., the municipality that includes Walkerton, said he is glad that important reforms have been made since the deadly drinking water contamination.

"The testing that occurs of the municipal drinking water in Ontario now is very rigorous," Chris Peabody said.

He said 35 people currently work at the Walkerton Clean Water Centre where operators from across Canada are trained on how to provide safe and clean drinking water.

But Peabody didn't want to speak further about the tragedy from 25 years ago, saying it was a traumatic experience for so many people.

Bruce Davidson, the Walkerton resident, said even though the E. coli illnesses in his family weren't as serious as many others, they have all been struggling with the consequences.

He said his wife had sporadic but "excruciating pain" and severe cramping for around three years, and he and his son are still experiencing "days when you just don't really want to get too far from a washroom."

The community has largely moved forward, he said. Housing has expanded and so have schools. The water is probably safer than anywhere else in the province, he said.

After the tragedy, a few residents decided to leave Walkerton but most — including Davidson — stayed.

"Most people looked at it and said, this community is our home. It is worth fighting for," he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 17, 2025.

Sharif Hassan, The Canadian Press